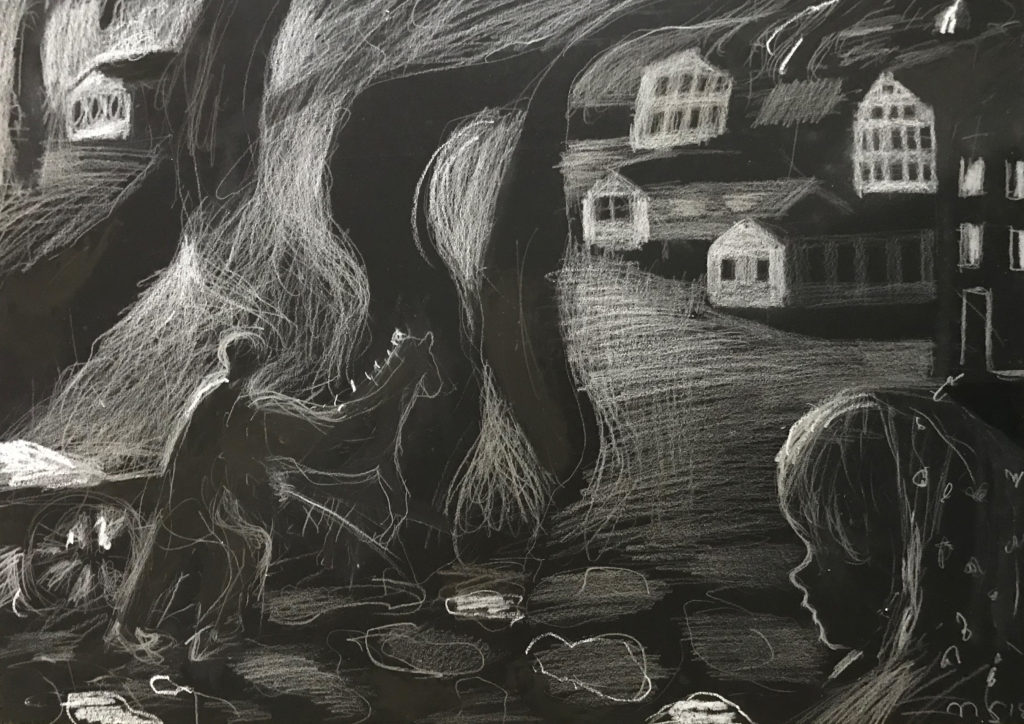

FIVE STREETS by Julia R. Gordon, with drawings by Noah Saterstrom

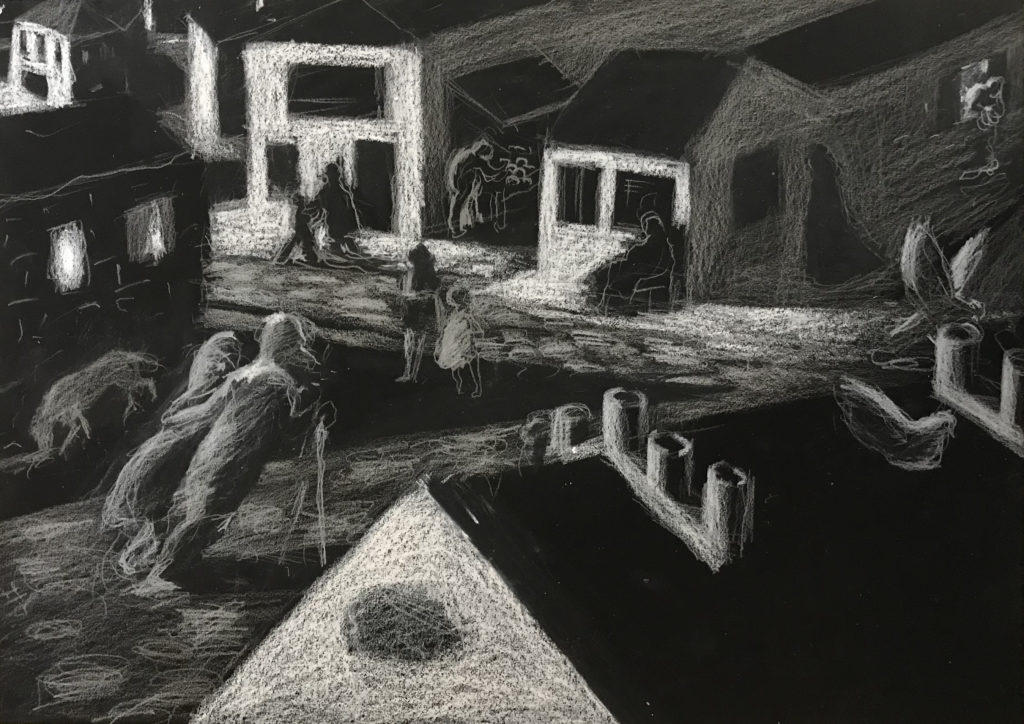

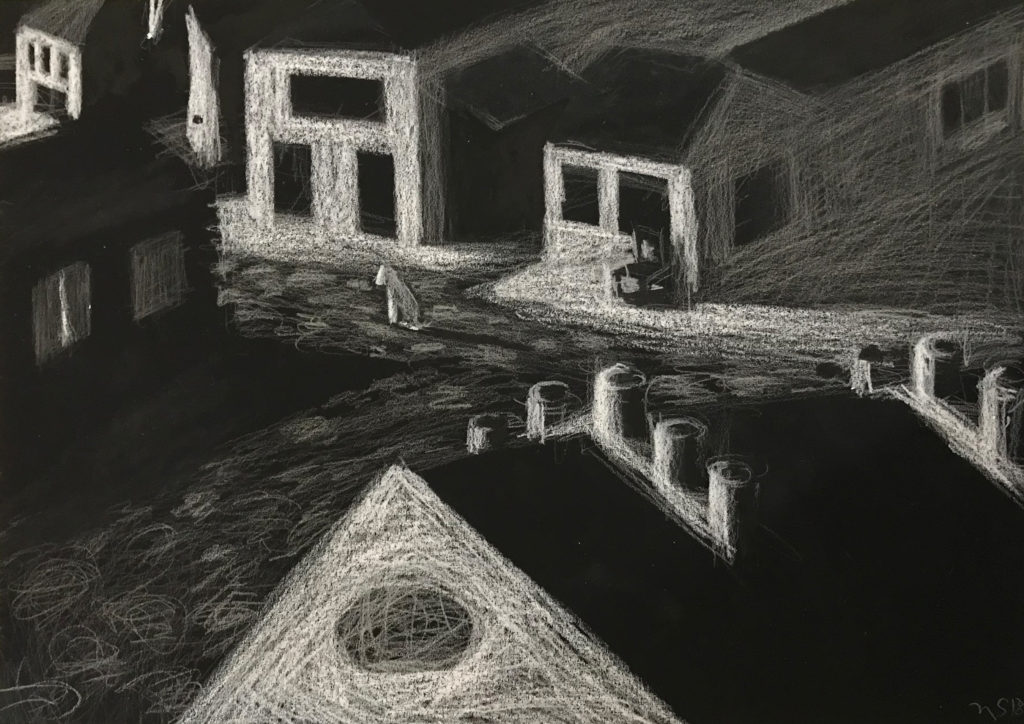

They live in a city, but the kind that has only five intersecting roads and is surrounded, otherwise,

by vast plowed fields and hundred year homesteads. Downtown means one street of shops:

grocer, butcher, dressmaker, baker; one street of words: bookseller, newsstand, library; one street

of medicine: doctor, apothecary, hospital, asylum; one street of god: two churches, three

synagogues, a large gathering hall. The fifth street is shadowed and not easily traversed, its

cobbles in constant disrepair; it is littered with those who have no homes and no gods but instead

have reaching arms and begging voices. Grime collects in the corners of windowless rooms

furnished with only beds and basins.

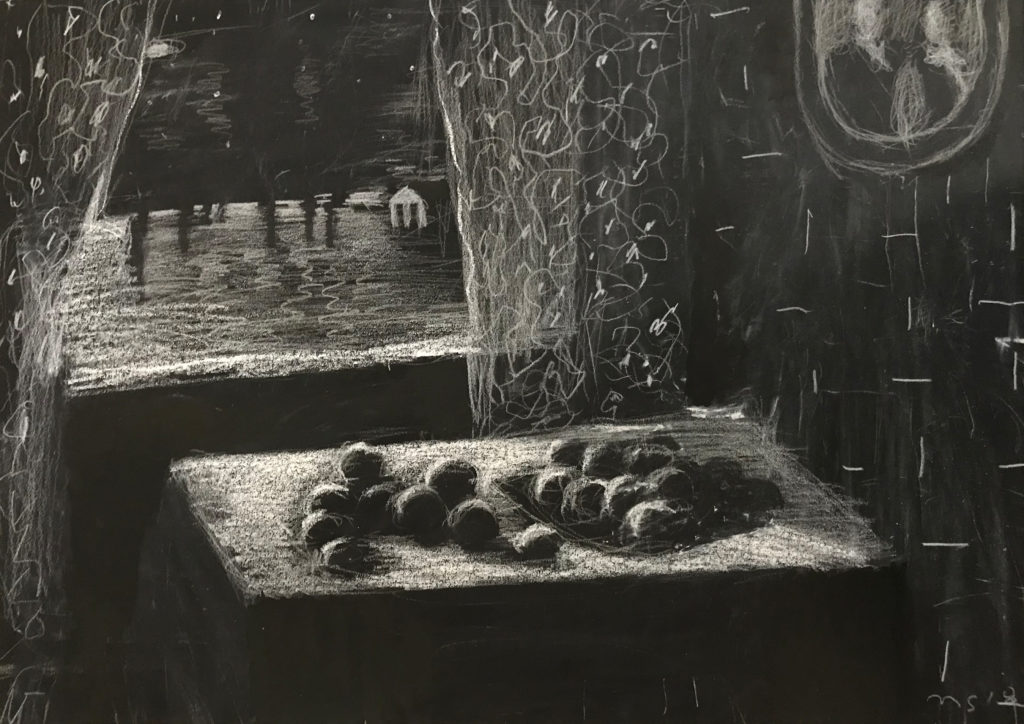

It is on this fifth street that they find a place to meet – a basement coated in thick dust and the

faint musty smell of newborn rats and cobwebs. They figure that the newly installed officers

won’t come here looking for their place of planning, and they are right. All through the long

winter of breaking glass and scorched shop streets, the fifth street gives them cover in its filth.

They meet at different times and on different days, planning, always plotting, within the

basement’s dank stone walls. The notices of their gathering times are carried from kitchen to

kitchen by young girls in aprons who hold napkin-covered baskets filled with hot bread rolls

layered atop slips of paper carrying coded messages of what, the girls do not know.

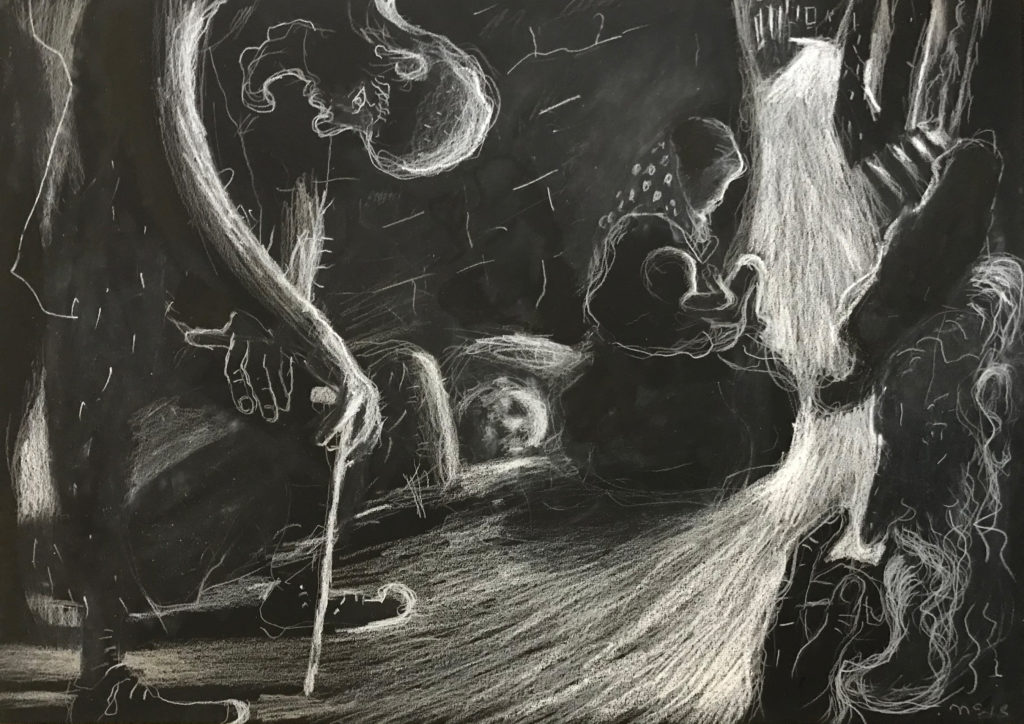

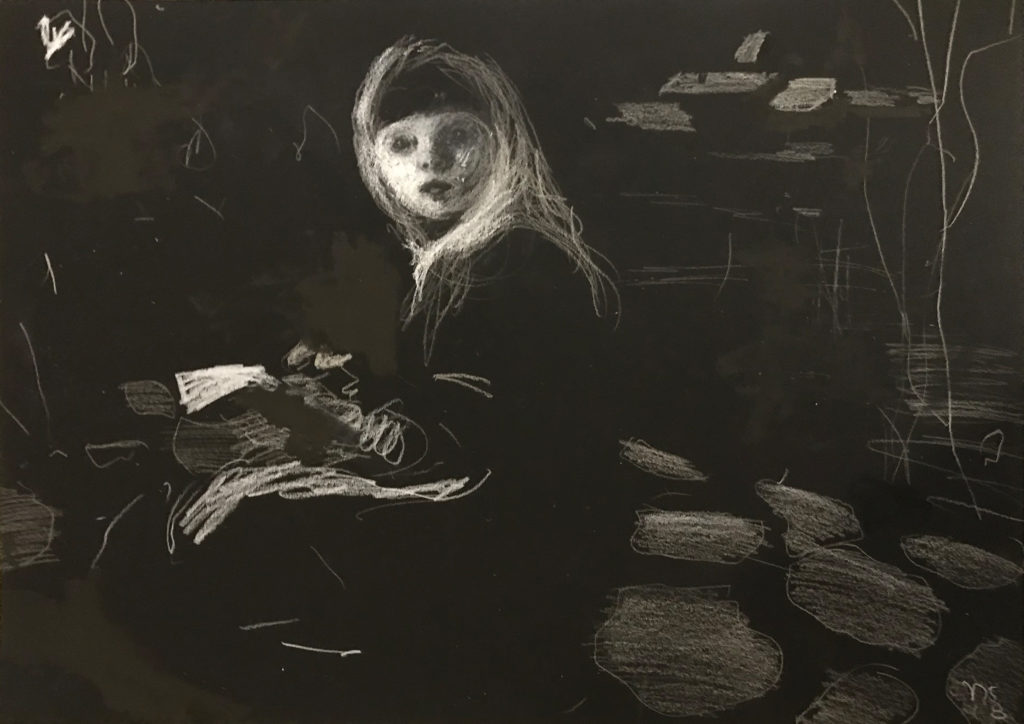

Most of these girls, given the papers by their fathers and the breads by their mothers, put

kerchiefs on their heads and shawls around their shoulders and follow well-trod paths to the next

kitchen over, dropping baskets on their way, having left the messages unexamined, cyphers

unbroken. She does not. She has been taught to read, and these coded missives, with their

strange transpositions and substitutions, are too enticing for her to ignore. She stashes a broken

slate and pencils in an old log between her house and the Brody’s farm, and for three days copies

the nonsense letters in sequence. She also eavesdrops. She listens to the Brody father’s

whispered murmurs to his sons when they think she is out of earshot; in her mind, she compares

what she hears with her own father’s murmurs to her mother, and thinks she begins to understand.

On the chosen day she lies awake, waiting, fully dressed under the bedclothes. The back of her

knees itch where her woolen stockings pill against the covered mattress ticking. When the moon

rises past the top of the chimney she hears it: a stirring downstairs, the heavy tread of her father’s

boot and the lighter, canted tread of her brother’s limp. Folding the covers back, she eases

herself out of bed and moves silently through the house and into the night, keeping the men in

her sight but lagging just far behind enough to avoid being seen. She follows them to the fifth

street. She presses her ear to a basement-level vent carved from the stone above one particular

basement annex and listens.

The men inside do not hear her but minutes pass and then hours, and she hears too much. Before

they have finished, she learns she was right and now she understands the fullness of their plans,

the whole of their murmured secrets of resistance and revolution. Heart beating, she runs back,

down the fifth street, past the shop street, the medicine street, and the god street, up the street of

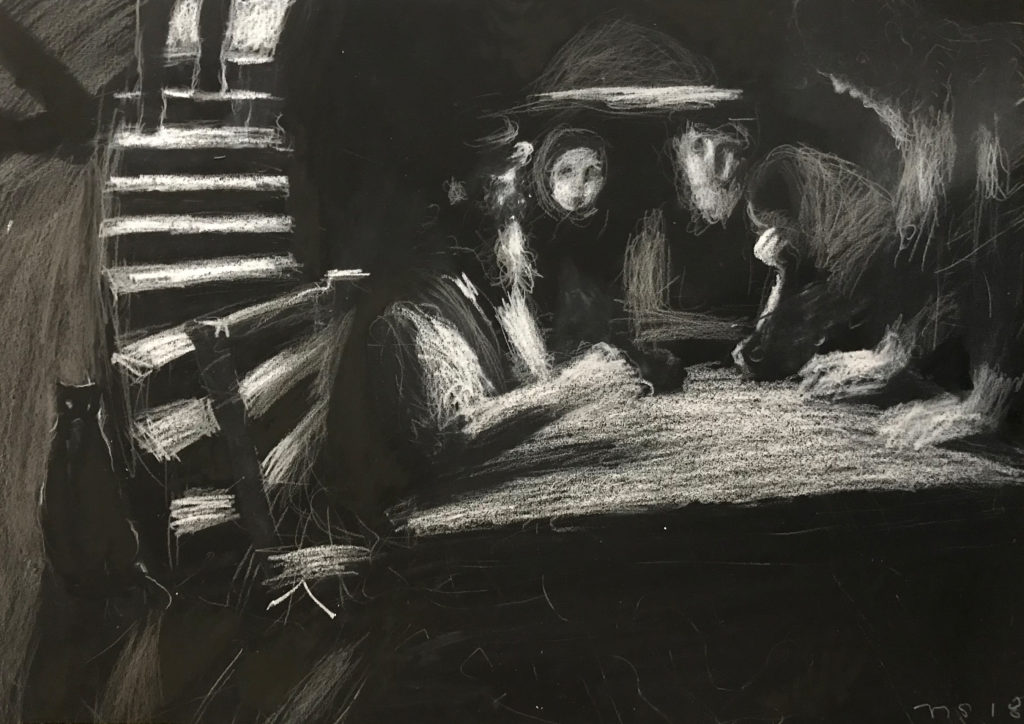

words and back to the kitchen where her mother sits awake, watching and waiting. Though she is

startled by her daughter’s appearance, the mother is not surprised by it but resigned to it, and the

girl rushes in to the embrace of raised arms. Her father and brother hew close behind, but they

did not see her flight and are thus shocked to find her, dressed in her shawl and kerchief, face

buried in her mother’s neck, arms clutching her mother’s thin shoulders.

It does not take long for them to discover the extent of what she knows. It does not take long for

them to determine that she is unsafe, all twelve spindly years of her, and it does not take long for

them to realize that in her youth, she is the most vulnerable of them all. It does not take long for

them to decide she must go. It does not take long for them to book her passage on a ship to

somewhere that is, if not safe, than at least away. And then, she is gone. Dandelion plucked from

the vast fields and the five streets and the Brody’s farm. The messages are carried, but without

her basket to cradle them. The meetings are held, but without her bearing witness. It does not

take long until it is almost as though she was never there. She is gone.

Soon another unexpected listener will hear the plans, but intent means much, and it is then that

the resistance, too, will be gone, ripped from the vast fields and the five streets and the Brody’s

farm. The soldiers will come, thick-booted and armed, and they will all be gone: fathers,

mothers, brothers, the other girls, their shawls and their kerchiefs, their bread. It will be almost

as though they were never there. It does not take long.

“Five Streets” is a group of drawings which illustrate a short story written by Julia R. Gordon. The tale is a fictionalized amalgam of the stories she heard throughout her childhood detailing her family’s life in Vilnius, Lithuania, under the late-19th century rule of the Russian Empire. Part of the intellectual, Jewish resistance against increasingly anti-Semitic Russian Czars, and under threat of pogroms, loss of land, and loss of life, the majority of her family fled to the New World as part of the general exodus of European Jewry in the early 1900’s. Those who stayed were ultimately slaughtered under the German occupation. Her great-grandmother, depicted in the story as the young girl unwittingly (at first) ferrying messages for the resistance, was one of the first family members to escape to New York as part of a forced flight when her family’s political involvement was discovered by the Russians.